'There's a huge amount that we don't understand': Why sperm is still so mysterious

How do sperm swim? How do they navigate? What is sperm made of? What does a World War Two codebreaker have to do with it all? The BBC untangles why we know so little about this mysterious cell.

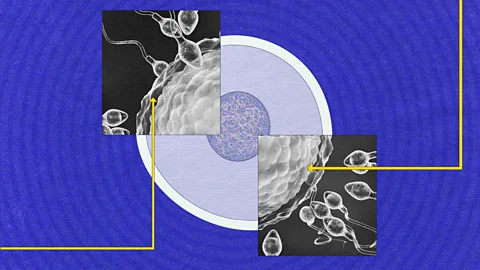

With every heartbeat, a man can produce around 1,000 sperm – and during intercourse, more than 50 million of the intrepid swimmers set out to fertilise an egg. Only a few make it to the final destination, before a single sperm wins the race and penetrates the egg.

But much about this epic journey – and the microscopic explorers themselves – remains a mystery to science.

"How does a sperm swim? How does it find the egg? How does it fertilise the egg?" asks Sarah Martins da Silva, clinical reader of diabetes endocrinology and reproductive biology at the University of Dundee in the UK. Almost 350 years on from the discovery of sperm, many of these questions remain surprisingly open to debate.

Using newly developed methods, scientists are now following sperm on their migration – from their genesis in the testes all the way to the fertilisation of the egg in the female body. The results are leading to groundbreaking new discoveries, from how sperm really swim to the surprisingly big changes that occur to them when they reach the female body.

"Sperm – or spermatozoa – are 'very, very different' from all other cells on Earth," says Martins da Silva. "They don't handle energy in the same way. They don't have the same sort of cellular metabolism and mechanisms that we would expect to find in all other cells."

Due to the huge range of functions demanded of spermatozoa, they require more energy than other cells. Plus sperm need to be flexible, to be able to respond to environmental cues and varying energetic demands during ejaculation and the journey along the female tract, right up until fertilisation.

Sperm are also the only human cells which can survive outside the body, Martins da Silva adds. "For that reason, they are extraordinarily specialised." However, due to their size these tiny cells are very difficult to study, she says. "There's a lot we know about reproduction – but there's a huge amount that we don't understand."

Alamy

AlamyOne fundamental question that remained unanswered over almost 350 years of research: what exactly are sperm?

"The sperm is incredibly well-packaged," says Adam Watkins, associate professor in reproductive and developmental physiology at Nottingham University in the UK. "We typically thought of the sperm as a bag of DNA on a tail. But as we've started to realise, it's quite a complex cell – there's a lot of [other] genetic information in there."

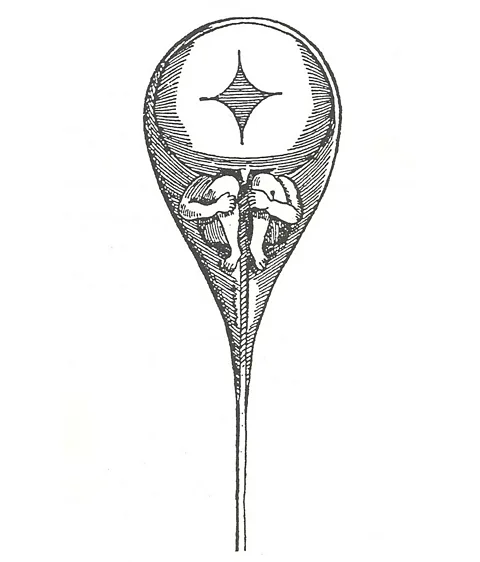

The science of sperm began in 1677, when Dutch microbiologist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek looked through one of his 500 homemade microscopes and saw what he called "semen animals". He concluded, in 1683, that it wasn't the egg that contained the miniature and entire human, as previously believed, but that man comes "from an animalcule in the masculine seed". By 1685, he had decided that each spermatozoon contains an entire miniature person, complete with its own "living soul".

Almost 200 years later, in 1869, Johannes Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss physician and biologist, was studying human white blood cells collected from pus left on soiled hospital bandages when he discovered what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei. The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually became "deoxyribonucleic acid" – or "DNA".

Aiming to further his studies of DNA, Miescher turned to sperm as his source. Salmon sperm, in particular, were "an excellent and more pleasant source of nuclear material" due to their particularly large nuclei. He worked in freezing temperatures, keeping laboratory windows open, in order to avoid deterioration of salmon sperm. In 1874, he identified a basic component of the sperm cell that he called "protamine". It was the first glimpse of the proteins that make up sperm cells. It took another 150 years, however, for scientists to identify the full protein contents of sperm.

Since then, our understanding of sperm has moved on leaps and bounds. But much still remains a mystery, says Watkins. As scientists have started to better understand early embryonic development, he adds, they are realising that sperm doesn't just the father's chromosomes on, but also epigenetic information, an extra layer of information that affects how and when the genes should be used. "It can really influence how the embryo develops and potentially the lifelong trajectory of the offspring that those sperm generate," says Watkins.

Sperm cells begin to form from puberty onwards, made in vessels within the testicles called seminiferous tubules.

"If you look inside the testes where the sperm are made, it starts as just a round cell that looks pretty much like anything else," says Watkins. "Then it undergoes this dramatic change where it becomes a sperm head with a tail. No other cell within the body changes its structure, its shape, in such a unique way."

It takes sperm about nine weeks to reach maturity within the male body. Unejaculated sperm cells eventually die and are reabsorbed into the body. But the lucky ones are ejaculated – and then the adventure begins.

After ejaculation, each of these tiny cells must propel themselves forward (alongside their 50 million competitors) using their tail-like appendages to swim for the egg. And while you may have seen plenty of videos of tadpole-like sperm swimming around, in fact scientists are only just beginning to understand how sperm really swim.

Alamy

AlamyIt was previously thought that the sperm's tail – or flagellum – moved side to side like that of a tadpole. But in 2023, researchers at the University of Bristol in the UK found that sperm tails follow the same template for pattern formation discovered by mathematician and World War Two codebreaker Alan Turing.

In 1952, Turing realised that chemical reactions can create patterns. He proposed that two biological chemicals moving and reacting with each other could be used to explain some of nature's most intriguing biological pattern formations – including those found in fingerprints, feathers, leaves and ripples in sand – an idea known as his "reaction-diffusion" theory. Using 3D microscopy, the Bristol researchers discovered that a sperm's tail – or flagellum – undulates, generating waves that travel along the tail to drive it forward. This is significant as understanding how sperm move can help scientists to understand male fertility.

So, now the sperm are on the move. They travel through the cervix, into the womb and up the oviducts – tubes that eggs travel down to reach the womb, known as the fallopian tubes in human females – in search of the egg. But here we hit another gap in knowledge, because scientists don't fully understand how sperm actually find their way to the egg.

Spermatozoa which are healthy and take the right route are rare. Many take a wrong turn in the maze that is the female body – and never even make it near the goal line. For the ones that do find their way to the fallopian tubes, scientists think that they may be guided by chemical signals emitted by the egg. One recent theory is that sperm may use taste receptors to "taste" their way to the egg.

Once the sperm find the egg, the challenge is not over. The egg is surrounded by a triplicate coat of armour: the corona radiata, an array of cells; the zona pellucida, a jelly-like cushion made of protein; and finally the egg plasma membrane. The sperm cells have to fight their way through all the layers, using chemicals contained in their acrosome, a cap-like structure on the head of a sperm cell containing enzymes that digest the egg cell coating. However, what prompts the release of these enzymes remains a mystery.

Next the sperm use a spike on their "head" to try and break their way in to the egg, thrashing their tails to force themselves forwards. Finally, if one sperm makes with the egg membrane, it is engulfed and can complete fertilisation.

Human cells are diploid. This means they contain two complete sets of chromosomes, one from each parent. If more than one sperm were to fuse with the egg, a condition called polyspermy would arise. Nondiploid cells – ones with the incorrect number of chromosomes – would develop, a condition lethal to a growing embryo.

To prevent this from happening, once a sperm cell has made with it, the egg quickly employs two mechanisms. First, its plasma membrane rapidly depolarises – meaning it creates an electrical barrier that further sperm cannot cross. However, this only lasts a short time before returning to normal. This is where the cortical reaction comes in. A sudden release of calcium causes the zona pellucida – the egg's "extracellular coat" – to become hardened, creating an impenetrable barrier.

So, of millions of sperm that set out on the journey, only one – at most – gets to do its job. The sperm's epic journey culminates in its fusion with the egg. Today, researchers are still attempting to uncover the identity and role of cell surface proteins that could be responsible for sperm-egg recognition, binding and fusion. In recent years, several proteins have been identified – albeit in mice and fish – as being crucial for this process, but many of the molecules involved remain unknown. So, for now, how the sperm and egg recognise each other, and how they fuse are yet more mysteries that remain unsolved.

One way researchers are hoping to shed light on sperm is by studying species other than our own, says Scott Pitnick, a professor of biology at Syracuse University in New York. Human sperm cells are microscopic, so we can't see them with the naked eye. But some fruit fly species produce sperm cells 20 times their own body length. That would be like a man producing sperm the length of a 40m (130ft) python.

Pitnick engineers the heads of fruit fly sperm so that they glow. This means he can watch them as they travel through dissected female fly reproductive tracts, revealing new details about fertilisation at the molecular level.

"Why do males in some species make a few giant sperm">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });